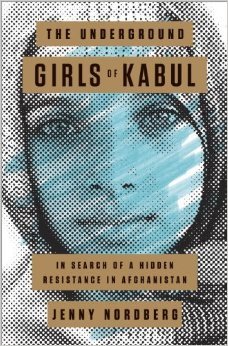

MLK Weekend Reading: Thoughts on Thinking & The Underground Girls of Kabul, by Jenny Nordberg

January 21, 2015When I first decided to host my own Martin Luther King, Jr. weekend read-a-thon, I knew I wanted to make an effort to immerse myself in books that would make me think. Though only one other person joined me for this RAT (hi, Karsyn!), I still enjoyed myself and managed to finish two books that had been making me think an awful lot.

I read other things, too—check out my announcement post for my closing stats—but I want to talk about one of those first two here: The Underground Girls of Kabul: In Search of a Hidden Resistance in Afghanistan, by Jenny Nordberg.

But before we get to that, a little aside about thinking. Dr. King himself was (unsurprisingly) a major advocate for critical thinking. Disillusioned by the current quality of education, then 18-year-old King, already a skillful writer, wrote an impassioned piece for his alma mater's college newspaper:

"To think incisively and to think for one's self is very difficult. We are prone to let our mental life become invaded by legions of half truths, prejudices, and propaganda. At this point, I often wonder whether or not education is fulfilling its purpose. ... Education must enable one to sift and weigh evidence, to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction." - The Maroon Tiger, Morehouse College student paper, 1947I've mentioned before that I'm a scientist by training and trade (OK, more like a scientist's assistant, but close enough for our purposes). While I'm a big fan of consuming information, I try my best to be skeptical of what I take in, both the facts themselves and from whom and/or where I'm getting them. Accumulating knowledge is a worthy goal, but even more meaningful is being able to extend that knowledge to other topics and to be able to pick apart the sensationalism in our chosen media and uncover the kernels of truth (or untruth) beneath. I very much try to keep this in mind when I'm reading, and particularly when I'm reading non-fiction or historically-based fiction.

Like Dr. King said, this is hard. Really hard. It becomes even harder when you're reading mainly for pleasure—it's way too easy to be lazy and nod along with whatever the author is saying. It's tough to know whether you're getting the reality of the thing, rather than just another convenient story or flawed way of thinking. This may not be out of malice or a specific agenda on the author's part—everyone has a different worldview, shaped by their communities and their experiences, and that gets reflected in their writing, for better and for worse. But, above all, it's important to be aware of this.

So, TL;DR: Try your best not to be a lazy consumer. Read whatever you like, but be mindful while doing so and definitely don't discount those times when you think to yourself, "Hmm, something isn't quite right here."

Now, on to this book, which happens to be non-fiction. I'll be getting up a review for the other—Growin' Up White by Dwight Ritter—on another day.

The Underground Girls of Kabul tells the story of reporter Jenny Nordberg's five-year attempt to report on the phenomenon of Afghanistan's bacha posh—literally translated as "dressed like a boy." As she discovers, dozens of Afghan girls are brought up as boys under the premise that, eventually (perhaps when their mothers bear "real" sons, as bacha posh are supposed to ensure), they will "change back." In addition to being used as fertility charms, these girls and young women help their family businesses and act as chaperones for female family members. They are also free to move around outside their homes, play with other children and make their voices heard, all unthinkable activities for girls. The stories of these women are interwoven with Afghan history and tradition, including Soviet and American attempts to modernize the country, the rise and fall of the Taliban, and the function of women in a largely patriarchal society.

The women—some of whom have "returned" to being women, while others struggle against it—lead inspiring and heartbreaking lives. I think particularly of teenager Zahra's refusal to relinquish her boy-turning-manhood, much to the chagrin of her parents and teachers. At one point, Nordberg asks her if she would wear feminine dress if she lived in the West:

She shakes her head at me in disbelief. "Don't you understand? I am not a girl."A big takeaway here is that not all bacha posh are created equal: some exist for family honor, aware (and accepting) of the fact that they will one day change back. Others, like Zahra, resolutely cling to their male status. Nordberg briefly veers into discussion of gender identity and trans issues, though not enough for my liking. An interesting, if fraught, question she raises is the role of nature and nurture when it comes to gender identity in Afghanistan:

What also makes Zahra distinctly different from other children or young adults in the Western world with a possible gender identity disorder is that she was picked at random to be a boy. As with other bacha posh, the choice was made for her. For that reason, it would be hard to argue that she was born with a gender identity issue. Instead, it seems as though she has developed one.Zahra's mother mentioned that her daughter expressed interest in wearing boys' clothes. She did not object, as she was hoping it would encourage a male pregnancy. I'm not sure that I would agree with Nordberg's assessment of "at random" in this case, but her point could certainly hold weight for other bacha posh.

A somewhat critical review of this book touched on the fact that Nordberg seemed to struggle with how to handle Islam's role in perpetuating Afghanistan's male-dominated society. Another laments that the academics and experts she spoke to were almost exclusively foreign-born. (I don't buy into the latter one as much, since the rampant oppression of Afghan women and sexuality doesn't seem to leave much room for female or gender studies scholars.) I know next to nothing about Islam or Afghan scholars and would have to learn more before I could consider whether she presented a balanced account. Does anyone have any recommendations for where to begin?

More than anything else, this book was a discussion of women's liberties (or, more accurately, the lack thereof) in Afghanistan. Privileges women in Western countries take for granted are only possible for Afghan women who are willing to run the risk of impersonating men. It was also a thoughtful meditation on what it means to be a woman—biologically, socially and personally. It serves as a reminder that many of the supposed "differences" between men and women are ones that humans constructed for themselves. I would recommend it for anyone interested in learning more about Afghan society and history and taking a critical look at gender roles and politics.

4 comments

Wow, this sounds so interesting, oh my god. I had never heard of bacha posh before, and I'm not sure I entirely understand what it is, but I guess that means I should read the book! I'm definitely into gender identity stuff.

ReplyDeleteYes, definitely check this out when you're in the mood for some non-fiction! Like I said, she doesn't get as deeply into gender identity/trans issues as I'd like, but it's fascinating nonetheless.

DeleteA manifesto for the future that is grounded in practical solutions addressing the world’s most pressing concerns: Jenny Nordberg, Underground Girls, Reporter Jenny Nordberg & Nordberg briefly veers.... buy college research papers online

ReplyDeleteIf you’ve watched the news this year, then you probably have a good idea how important this writer is to companies and the government – as Jenny Nordberg and Underground Girls.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.assignmentcompany.com/homework-assignment-service